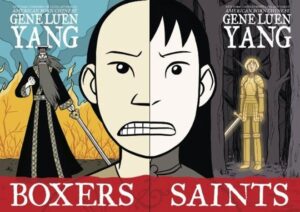

I did a class that focused on the Boxers last semester, and one of the things I talked about was Gene Luen Yang’s Boxers and Saints.

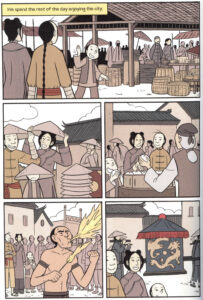

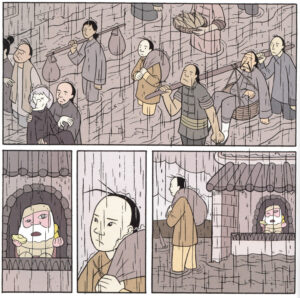

This is a two volume graphic novel that looks at the Boxer event. How good is it? Well he has done his research. Cohen’s History in Three Keys was our main text and it is in Yang’s bibliography, as is Esherick’s Origins of the Boxer Uprising. It shows in the text. If you want to show your students pictures of Chinese peasants being flooded out of their homes

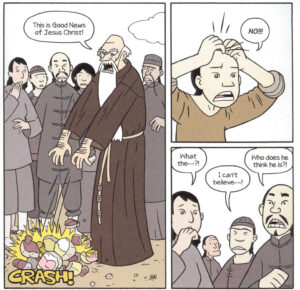

Or foreign missionaries being obnoxious

this is your book. The main focus of Boxers is Bao, who grows from a random peasant boy to a redresser of wrongs who will save China and maybe even get the girl.

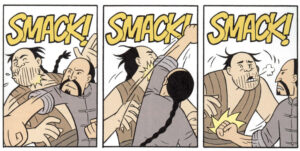

Visually I am not sure Yang’s style works as well as it could with the subject matter. Early on Bao discovers that his dad is in fact a gongfu hero.

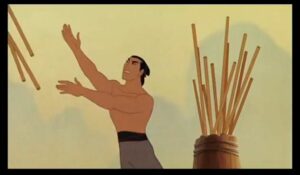

Who apparently studied under Adam West. Yang has a fairly limited style which does not lend itself to the martial arts, especially given what a lot of other people have done with them in Manga. Yang actually seems more influenced by American animation traditions.1 He has two scenes where a gongfu master announces the beginning of the lesson by tossing weapons at the students,

which reminded me of this.

A lot of the themes are pretty American as well.

Much of first volume deals with Bao’s growing relationship with Mei, a local girl who will eventually becomes the Action Girl leader of the Red Lanterns.

The romance story is hard to square with the Boxers and their misogyny, and Yang is aware of this, but he does not help himself with things like this rom-com montage sequence, were Bao and Mei amuse themselves like American tourists by eating at stalls and wearing peasant hats, just like Chinese people.

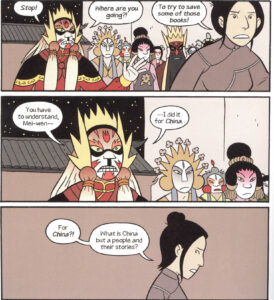

His style does work well for some things. Possession rituals were an important part of Boxer magic, and Yang has done his homework. Here is the ritual

And here is a possession.

Bao himself is possessed by Qin Shihuang, who is not an opera character but can lecture Bao on the importance of saving the China he created.

These possessions are important to Yang since the attraction of the story for him is that the Boxers are like American geeks, living through their superheros. From Yang’s website

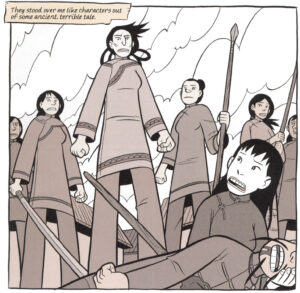

So where did these poor teenagers look for power? Like modern-day geeks, they turned to pop culture. They went to fairs and watched traveling acting troupes perform Chinese opera. Chinese opera told epic tales of colorfully-costumed heroes who fought evil with superpowers and magical weapons. The heroes of the Chinese opera were not unlike the heroes of modern American comic books, only instead of capes, flags flapped at their backs.

Like modern-day cosplayers, the teenagers wanted to embody their heroes. They came up with a mystical ritual that would call the heroes of the opera – the gods of the opera, really – down from the heavens. The teenagers would be possessed by the gods and take on their superpowers. Then armed with these superpowers, they marched through their homeland and into the major cities, battling foreigners.

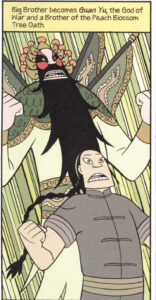

So the Brothers of the Peach Orchard become the Avengers. From Yang’s site, some superheros as Chinese opera characters.

The middle one is The Hulk. I’m pretty sure that Chinese opera already has a Hulk, and his name is Li Kui,

But you get the idea.

One of the major themes of Boxers is the growing relationship between Bao and Mei and how Bao’s commitment to violence splits him off from Mei’s commitment to culture. Yang does not to make the story too bloody, perhaps in part because his style is not really up to it.

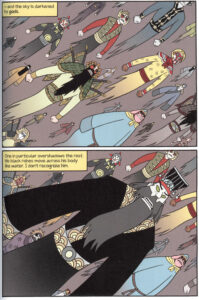

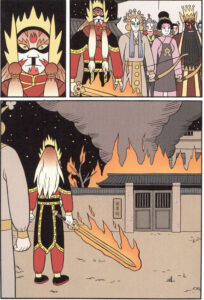

We do get battles

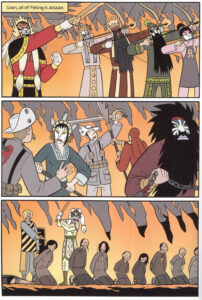

and Prince Gong drinking tea as Beijing burns

but actual violence tends to take place off-stage.

Mei tries to draw Bao towards the saving grace of China’s 5,000 years of culture.

But in the end they split over the issue of burning the Hanlin Academy library to get at the foreigners. Like with modern Americans, book burning is about as bad a thing as you can do.

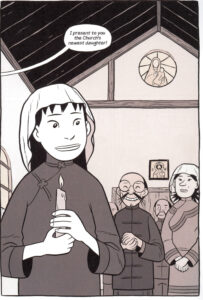

The real emotional heart of the story comes in Saints.

Here we see some of the scenes from the previous book from a different angle

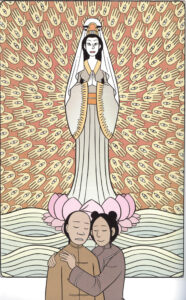

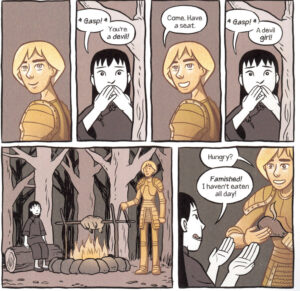

the center of Saints is Vibena and her conversion to Christianity2 , which is encouraged by her visions of Joan of Arc.

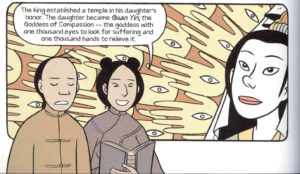

Yang draws visual parallels between Jesus and Guanyin (note the hands), showing a nice modern ecumenicism.

And picks a person addicted to foreign3 opium to lead Vibena to the faith, showing a darker side of the foreigners.

In the end, Bao’s gods can’t save him

and Vibena’s can, even after she has died. Yang is a Catholic and her conversion and martyrdom story is one that appeals to him.

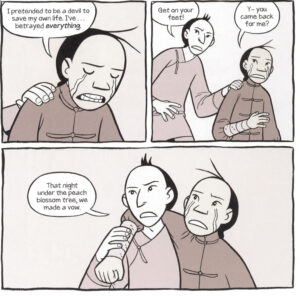

A brave man dies only once, but a superhero can die as many times as is convenient for the plot, and Bao is also saved by one of his Sworn Brothers.

Of these themes I think only comradeship is one that would have made much sense to the actual Boxers.

So, what did I think about teaching with this book? I don’t think I would use it in a Chinese history class, as it is too much of Yang reading Chinese history for his own purposes. I spend far too much time already trying to encourage students to figure out how Chinese might view their own history rather than asking what Americans can get out of it. This, however, was a course on historical method, using the Boxers as an event that lots of different people have looked at in different ways, and for that it worked pretty well.

Just another quick thanks for again turning me on to a new resource for my own teaching. Ordered both.