I have been preparing a paper for a conference here at IUP, but since the conference is postponed as we are on strike I thought I would share some of it with you here. The paper is “Zhang Guangyu’s Xiyou Manji (Manhua Journey to the West) (1945) and the Chinese Tradition of Visual Satire” and I am doing it for a conference on comics that our English department is hosting. Mostly I am just doing it to introduce some stuff about Chinese comics, leading up to Zhang’s 1945 work, which I would claim is maybe China’s first manhua, in the sense of a graphic novel1 For those of you who don’t know the work, Nick Stember has put the whole thing on-line. It is basically a wartime adaptation of Journey to the West.

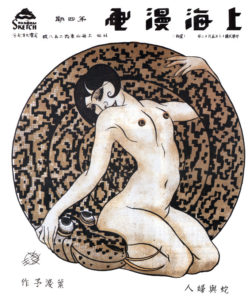

I talk about how Xiyou Manji is important in terms of format and design, but also in its criticism of the government. Zhang Guangyu, the author, had a long history as a manhua artist, and I look at the stuff he did and published as the editor of Shanghai Manhua

I talk about how Xiyou Manji is important in terms of format and design, but also in its criticism of the government. Zhang Guangyu, the author, had a long history as a manhua artist, and I look at the stuff he did and published as the editor of Shanghai Manhua

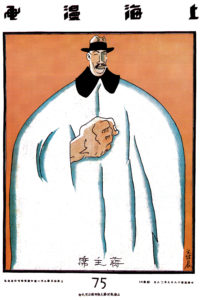

in 1928-1930. Manhua artists and magazines tended to get into political trouble, and they did post some stuff that would seem to lead to trouble, like this caricature of Chiang Kai-shek.

There were a couple of things that kept them on or near the right side of the censors, however. One was the fact that they tended at this point to focus on social criticism of the corruption in Shanghai society, a topic where Nanjing might agree with them, and they did it is a foreign, modernist idiom that was not likely to get much traction with the masses.

There were a couple of things that kept them on or near the right side of the censors, however. One was the fact that they tended at this point to focus on social criticism of the corruption in Shanghai society, a topic where Nanjing might agree with them, and they did it is a foreign, modernist idiom that was not likely to get much traction with the masses.

The other thing was that things like caricatures were clearly critical, they were not very pointed. Apparently you could get away with vague criticisms of leaders, but not with specific policy criticisms.

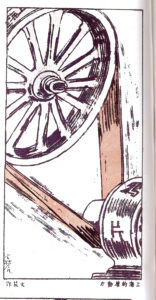

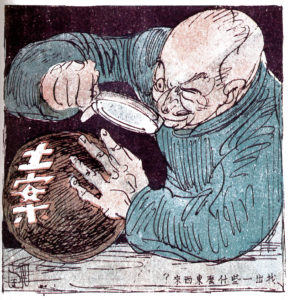

The closest I found to policy criticism in Shanghai Manhua was their treatment of the 1929 Jiangan opium case, in which a shipload of opium that was pretty clearly being protected by someone high up in the government was seized. The case was never never solved, and2

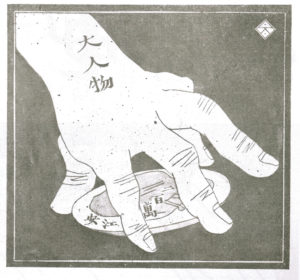

There were plenty of cartoons about it. Here we have “powerful people” grabbing opium money

and here we have opium as Shaighai’s motor.

What we don’t get is much specific criticism of these important people. Who is responsible for this case? Its a mystery!

We do eventually get some things about minor figures involved in the case, but this is a long was from the type of explicit stuff cartoonists will do later, and that Zhang will do in 1945. A number of scholars have called the Shanghai manhua apolitical, and I think that is clearly wrong, a lot of their social criticism stuff is clearly political. Still, the political stuff they do is far less pointed than what will come later.

Part 1 of …..

And now, just for the fun of it, a 1911 cartoon of Zhong Kui the demon queller on his bike from 19113

I am not that hung up on “firsts”, but for this paper it works. ↩

There is a bit more on the case here Baumler, Alan. The Chinese and Opium under the Republic: Worse Than Floods and Wild Beasts. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. p.136. ↩

from Bi Keguan, Huang Yuanlin Zhongguo manhua shi Beijing: Wenhua yishu chubanshe, 1986 ↩