I stumbled across the American traveler William Edgar Geil’s Eighteen Capitals of China (1911). I wasn’t impressed. Even for its time, it is particularly packed with stereotyped and dismissive descriptions of Chinese people, never failing to take the opportunity to make fun of some aspect of the locals he comes across.1

I stumbled across the American traveler William Edgar Geil’s Eighteen Capitals of China (1911). I wasn’t impressed. Even for its time, it is particularly packed with stereotyped and dismissive descriptions of Chinese people, never failing to take the opportunity to make fun of some aspect of the locals he comes across.1

The book has a chapter on Wuchang, one of three cities that make up Wuhan. The city on the eastern side of the Yangzi river was capital of Hubei province, and the centre of government and military infrastructure in the region. As for trade, Geil suggests “Officialism and commerce often thrive better with a little partition between.” He points to Hanyang and Hankou (Hankow) across the water, with Hankou’s relatively recently built walls on only one side making it a “hedgehog, prickly enough on one side, but quite defenceless on the other.” It is there the British, Russians, French, Germans, and Japanese have concession territories.

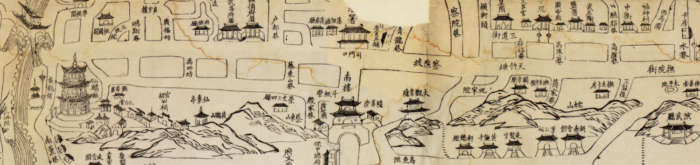

At the time of his visit (the intro claims he visited all the cities in his book) Geil claims that Wuchang made up only some 200,000 people of a total of a million in the three cities of Wuhan combined. He describes Wuchang’s long east-west “Serpent Hill” splitting the city and, in the west, a “Flower Hill” on which stands “a handsome three-story pagoda.” This may have be the building located on the site of the many-times-rebuilt Yellow Crane Tower (黄鹤楼 but towers there had a number of different names) and helps date his trip. The tower didn’t exist between 1884-1907, so one assumes his trip there was sometime between 1907-1911 when there was a 奥略楼 building near that location.2 Just north of this is an east west “spine” of seven thousand shops that are the “Broadway of Wuchang.” This map from 1883 is from an earlier time but I’m guessing that 察院坡 is what he is referring to. A 1935 essay on Wuhan by 王佐良 claims that the street was full of bookstores.

What I found amusing about the book, given its publication in 1911, was its confident narrative of a city that had experienced the frightening prospect of urban rebellion but was now firmly in more orderly times. In describing the policing of the city, Geil refers to an attempted rebellion in 1882. Although this may refer to a local Wuchang incident, I wonder if what he describes as a huge scare (“nine of ten disappearing to the country…servants had most appropriately taken French leave.”) was perhaps in fact referring to a failed rebellion in 1883, analysed in great detail in the final chapter of William Rowe’s Hankow: Conflict and Community in a Chinese City, 1796-1895. It goes on to describe another failed uprising by “red-republican anarchists” in 1900 who believed that their victory would “inaugurate a commonwealth of perfect equality and universal prosperity.” (p253)

After incidents like this, Geil concludes that “the danger sobered the people” and going forward,

“It is not likely that many more pranks of this nature will be tried. The Chinese military system is being recast, and the old methods are passed away. At Wuchang there are now large barracks in which a division of 20,000 soldiers are being trained. It is impossible to give a close account of the proceedings, but evidently the utmost care is being bestowed on them…” (p254)

There was at least one more “prank” of that nature which came in very short order. In October of the same year the book was published, and only two months after the book’s August dated forward, an uprising occurred which would include parts of the very new army that Geil was referring too. They would soon come under the command of Jackie Chan, I mean, under Huang Xing in one of the few military engagements of the revolution proper. This Wuchang uprising, on October 10, 1911 (“double ten” 双十 / 十十)would kick off the collapse of the Qing dynasty.

One of the entertaining aspects of the book, however, was the decision of its author to plant idiomatic expressions, with translations on almost every other page of the book. The Wuchang chapter included 小石頭打破大缸,不上高山不顯平地,相知滿天下知心有幾人,看花容易繡花難 ↩

This may show an image of the tower he saw, which resembles neither the tower that preceded it or the tower that stands there today. ↩